DEEP SOUTH DIVERS Explores the City of Savannah

Around here, the "Hurricane of 1893" is a significant part of our history. The incredible storm devistated a good portion of our small town, and flooded every local island, combined known as the "Sea Islands." As many as 12,000 local residents were killed, mostly from rising floodwaters and storm surge. At one point, it is said, all of the tomato, cotton, rice, and indigo plantations were totally submerged. Stories abound of finding dead bodies in the treetops for years after the hurricane.

This massive storm grounded and sank many ships as well - some not even from the area, but passing by on their way to larger ports like Boston, Savannah, Charleston and Philadelphia. Such was the case of the vessel known as a the City of Savannah, one of a fleet of three ships named after common shipping ports.

According to the book Sea Island Storm of 1893 By Bill Marscher and Fran Marscherthe:

As the hurricane traveled westward across the Atlantic, the 272 foot steamship City of Savannah had left Boston for Savannah on Thursday, August 24th, (1893) with Captain George Savage in command. She had about thirty people onboard, including two children and crew, and medium sized cargo. Starting out in a gale, the ship reached heavy seas from the southeast off Cape Hatteras Saturday and by three o'clock Sunday afternoon just off of the coast of Charleston was thrashing about in the teeth of the storm.

She lost her power, began to take water into the engine room and started drifting in the rough seas. By early Monday morning, she had been driven onto a sand shoal about 3 miles off Beaufort County's Fripp Island. As the passengers huddled together on the starboard (right) side, she began to take on water, and the waves demolished the saloon and gutted the cabins. The passengers and the crew spent Monday night lashed in the rigging. "The waves dashed over them and death was expected at any moment." (Morning News, August 31, 1893)

On Tuesday morning, Captain Savage sent two lifeboats to St. Helena Island, carrying the City of Savannah's women and children and two ship's officers to safe quarters there. Three riverboat pilots from Beaufort - John O'Brien, William VonHarten (yes, the same VonHartens as the modern Beaufort residents), and John L. Mack - tried to stage a rescue using a tug with a 10-foot draft. Just as they realized the water was so shallow they could not reach the grounded ship, they saw the steamship City of Birmingham (one of the City of Savannah's sister ships) on the horizon and hoped she would be able to save the endangered crew and passengers.

At about six o'clock Tuesday night the City of Birmingham anchored nearby. The water was too rough to attempt a rescue at that time, however, so the remaining passengers and crew spent another night lashed to the rigging with nothing to drink and only raw turnips to eat. At daybreak Wednesday, crews from the Birmingham began the rescue in earnest, and by noon, "those who had stared death in the face for thirty-six hours were safe aboard the Birmingham." Nearly crazed with thirst and dehydration, they asked first for water. Soon, they also had a meal - their first since mid-day Sunday. Captain Savage, the last man off the ship, carried a cat with one blue eye and one brown eye with him as he walked ashore.

After the Birmingham delivered them to Savannah, the captain slept a few hours before going to St. Helena Island in a tugboat to get the rest of his passengers and two crewmembers. On Friday morning, when the tug delivered the captain, the women, and the children to Savannah, a crowd of 1,000 Savannahians applauded and cheered from the bluff overlooking the Savannah River.

After the Great Sea Island Storm of 1893, the grandeur of the City of Savannah was no more. Attempts to salvage her failed. In a few years, she came to be called "The Wreck," a favorite fishing drop. Today sea bass and sheepshead feed on the barnacles that plaster her boilers, the only relics left of the once proud ship.

The wreck of the City of Savannah sits in a less-traveled area of our local waters, several miles and many treacherous shoals and shallows from any port, marina, or boat landing. As such, and despite it's well-documented history, its location had not been commonly known. The wreck is featured in Gary Gentile's book Shipwrecks of South Carolina and Georgia, which is considered to be a respected source of concrete information on local shipwrecks. However, the entry about the City of Savannah fails to pinpoint the wreck's location. Thus, DEEP SOUTH DIVERS contacted Gary Gentile and asked about specific location.

Gary is a well-publicized expert on shipwrecks, and considered by many to be a pioneering forefather of trimix - a technologically advanced breathing gas for deep diving. However, Gary professed to not know exact coordinates or even the ship's approximate location.

That's when DEEP SOUTH DIVERS contacted Robert Gecy of Humminbird Side Imaging Forums. Robert - or "Bobby" as he is known to us - knew of the wreck's location and took us there.

When we arrived at the wreck's location, this is what we saw:

The item sticking above the waterline at low tide is the ship's quadrant. This is a pie-shaped device welded to the top of the ship's rudder shaft. It normally sits within the bowels of the ship, directly above the ship's rudder, and is attached to a chain on either side of the quadrant. When the captain turns the steering wheel, the chains are pulled one way or the other, puling the quadrant in one direction or the other, which effectively changes the angle of the rudder. Now that the wreck has completely collapsed, the rudder and rudder shaft have supported the quadrant in such a way as to expose the entire quadrant at low tide.

More photographs of the ship's steering mechanism:

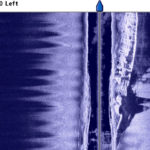

Additionally, Bobby made several sidescan images with his Humminbird scanning system. These are our favorite images of the wreck: